Economic growth stands as a central theme in global development. For decades, increasing national income has been the most powerful engine for lifting billions out of poverty and improving living standards worldwide.

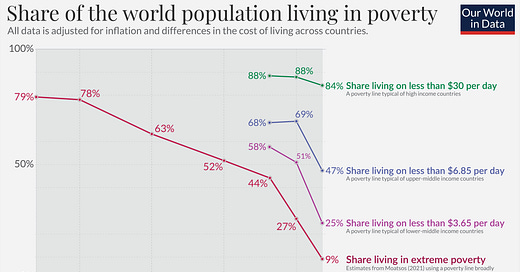

Sustained economic growth has fundamentally reshaped the world, driving dramatic improvements in health, education and access to goods and services previously unimaginable. Consider the scale of change: in 1820, around 75% of the world lived in extreme poverty; today, that figure is closer to 8.5%. Global average life expectancy has more than doubled in the same period. At its heart, growth involves an economy producing more of what people value, leading to higher incomes and resources for individuals and societies.

However, the pursuit of growth is complex, raising critical questions about sustainability, fairness and what constitutes progress.

What is Economic Growth & Why Does it Matter?

Economic growth typically refers to the increase in the market value1 of the goods and services produced by an economy over time. It's most commonly measured as the percentage rate of increase in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or Gross National Income (GNI). While total GDP reflects the overall size of an economy, GDP per capita2 is often more useful for understanding development, as it indicates the average resources available to individuals within a country.

Growth and Poverty Reduction

For centuries, sustained economic growth has been strongly correlated with dramatic improvements in human welfare. As countries get richer, they tend to see significant reductions in extreme poverty, lower child mortality, higher education levels and longer life expectancies. Global average life expectancy, for instance, has more than doubled from 29 years in 1820 to over 73 years today, largely driven by growth enabling better health, sanitation and nutrition.

Even modest incomes today grant access to goods and services unavailable to the wealthiest individuals just a few generations ago. As highlighted by Our World in Data below, economic growth is fundamentally about increasing the quantity and quality of these tangible goods and services that people need and want for a better life, from food and housing to healthcare, education, transport and communication. These goods and services are not just there; they need to be produced, and growth means their availability increases.

Historical accounts vividly describe the scale of poverty before such growth took hold, with widespread hunger, low life expectancy and vulnerability even to small economic shocks, highlighting the urgency of increasing productive capacity.

China is a prominent recent example. Since reforms began in the late 1970s, prioritising private business and exports, China experienced decades of rapid growth. This lifted nearly 800 million people out of extreme poverty, accounting for a significant portion of global poverty reduction in that period and transforming lives on an unprecedented scale. Although, this rapid growth sometimes involved significant social costs and challenging working conditions.

Despite progress, extreme poverty persists for nearly 700 million people, largely in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Growth in these regions is likely to yield disproportionately large welfare gains. A small percentage increase in income for someone living in extreme poverty can have a life-changing impact on their ability to afford food, healthcare or send a child to school.

Our World in Data - What is economic growth? And why is it so important? (15 minutes)

Key innovations and productivity increases (the printing press or those from the industrial revolution) have dramatically increased the availability and affordability of goods and services over time

Measures like GDP per capita or average income track the value or real income associated with this increased production and access. They are measures of growth, not the definition itself

Despite measurement challenges (like capturing quality changes or non-market production), these metrics show a clear picture of historical transformation

Average incomes were stagnant for centuries before rising dramatically, especially in the last 200-250 years

This era of growth coincided with an unprecedented decline in extreme poverty globally and improvements in health outcomes and education

Today, despite significant progress, global inequality is vast, and billions still live in poverty

Ending poverty requires further increases in the production and distribution of essential goods and services

Economic growth represents a crucial shift from a historical zero-sum economy to a positive-sum one, where widespread prosperity becomes possible

While the rate of growth is important, the direction (what is produced, how and for whom) is also key

While GDP per capita is a powerful indicator strongly correlated with these historical improvements it doesn't capture everything that contributes to human welfare (like leisure time or environmental quality). However its historical link to large-scale poverty reduction and improvements in health and education makes it a useful metric when discussing global development over the long term.

Engines of Growth: What Drives Economies?

Economists generally attribute long-run economic growth to a combination of fundamental factors that increase a society's capacity to produce goods and services.

Capital Accumulation

Increasing the stock of physical capital (machinery, factories, roads, power plants)

Labour Force Growth & Quality

Having more workers contributes to overall production

Improving the health and education of existing workers (enhancing human capital) makes each worker more productive

Technological Progress & Innovation

This is often seen as the most important driver of sustained per capita growth in the long run

It involves discovering more efficient ways to produce existing goods and services, creating entirely new products or improving the quality of what's produced

Think of the impact of electricity, the internet or new agricultural techniques

Institutions & Governance

Stable political systems, secure property rights, predictable rule of law, effective regulation and low levels of corruption create an environment where businesses are willing to invest, entrepreneurs are willing to innovate and people trust the economic system

Weak institutions can stifle growth, even if other factors are present

These broad factors manifest in specific areas that are particularly important for fostering growth in LMICs.

Infrastructure

Reliable transport networks, communications systems and energy supply are essential for businesses to operate and for people to access markets and services

Trade (Import/Export)

Engaging in international trade allows countries to specialise in producing what they are relatively best at, access larger markets beyond their domestic size (enabling economies of scale) and gain access to new technologies and ideas from abroad

Export-oriented manufacturing has historically been a key pathway for many economies to integrate into the global market and accelerate growth

Finance

A well-functioning financial sector (banks, markets) directs investment to productive uses and manages risk, facilitating business expansion and innovation

Innovation Ecosystems

Creating environments that support research and development, encourage entrepreneurship and facilitate the adoption of new technologies is key for long-term productivity gains

One perspective on how these elements combined to drive rapid development in East Asia proposes a three-part model (from How Asia Works).

First, land reform, taking farmland from large landowners and giving it to peasant farmers. This is argued to address inequality and productivity, as small farmers may work the land more intensively to maximise yield per unit of land, which is vital in labour-abundant economies

Second, focused industrial policy combined with export discipline. This involves state support for specific manufacturing industries (often infant industries protected by tariffs) coupled with requirements for firms to sell a significant portion of their products internationally. This push for exporting is argued to force firms to become competitive and reveal which ones are succeeding at learning their industry

Third, financial policy designed to serve the needs of agriculture and manufacturing. This includes directing finance towards productive investments rather than speculation and often involves strict capital controls to manage flows and maintain incentives

Other models of development exist, but this highlights a specific proposed sequence and combination of interventions.

Criticisms & Complexities of Growth

While the historical link between economic growth and improved living standards for billions is strong, the pursuit of growth faces significant criticisms.

Growth vs. Distribution: Who Benefits?

A major criticism is that economic growth doesn't automatically benefit everyone equally. Growth can sometimes coincide with rising income inequality, leaving certain groups behind or even worse off. The impact depends heavily on how the wealth generated by growth is shared through wages, social spending and tax policies. Accounts of pre-growth poverty, marked by extreme inequality in land ownership and exploitative practices, underscore this challenge.

Inequality is largely a result of policy choices and structural factors within an economy, rather than an inevitable consequence of growth itself

Global inequality (between countries) has decreased over the past few decades (largely due to growth in countries like China/India), while inequality within many countries has increased

The world is far too poor to end poverty without large growth.

85% of the world's population lives on less than $30 per day, with 77% living in countries where over 90% are poor by this standard (in 2017 when this chart was made)

To reduce global poverty substantially (to Denmark's level of 14% living below $30/day), the global economy would need to grow by at least 410%, or become 5.1 times larger

Ethiopia's average income of $3.30/day would need to increase 16.7-fold to reach Denmark's $55/day average

This calculation assumes perfect redistribution from rich to poor countries and equality improvements everywhere, real-world growth needs would be even higher

If we were able to redistribute the wealth of the richest 500 people (~$10 trillion) globally, that would be approximately $1,220 per person (as a one off payment)3

Environmental Costs

Economic activity, historically powered by fossil fuels and resource extraction, has led to environmental consequences, including climate change, air and water pollution, and biodiversity loss. Critics argue that continued growth is unsustainable.

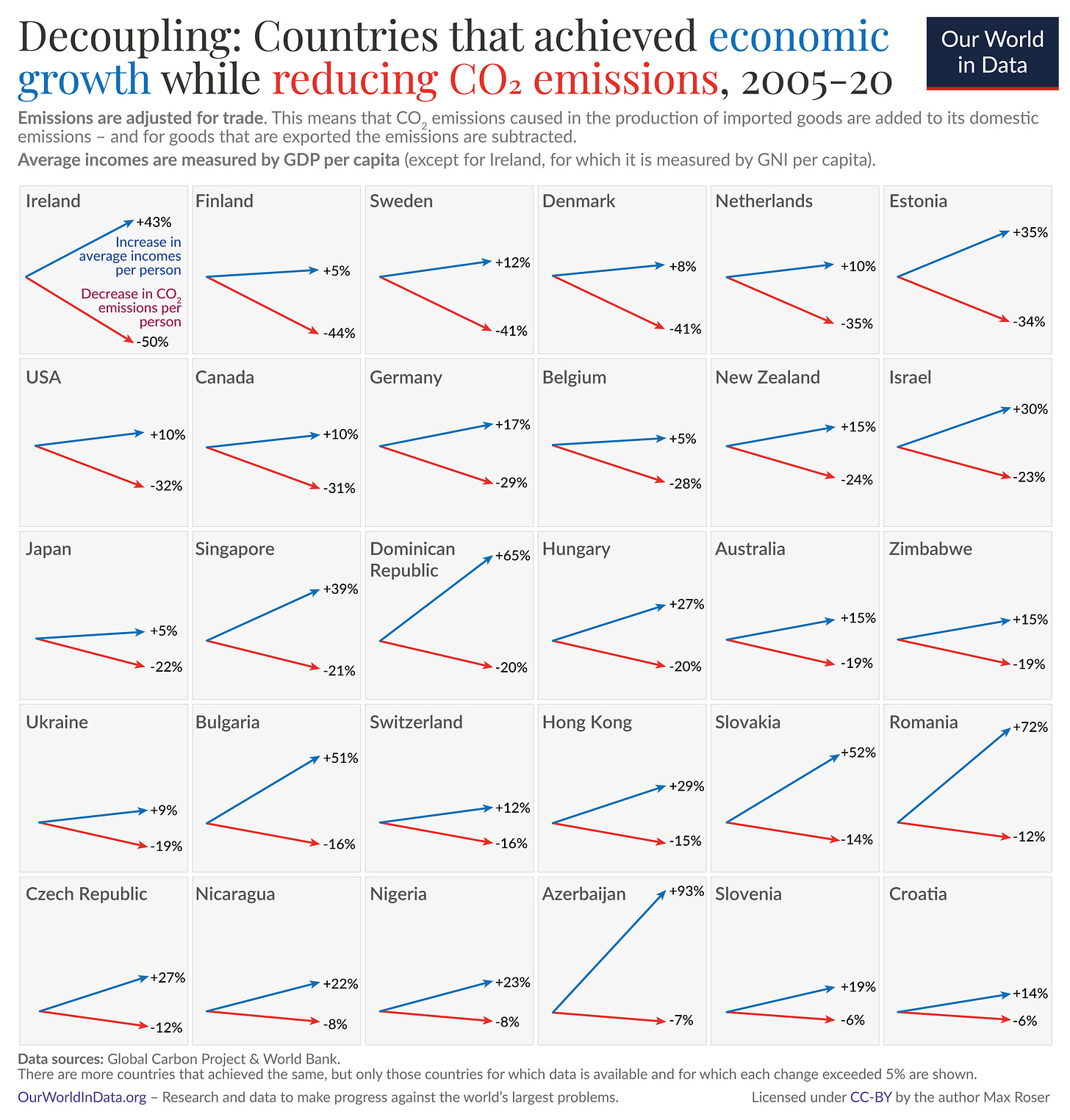

While the link between historical growth and environmental damage is clear, it's important to note that economic growth is not inherently tied to environmental destruction

Decoupling, increasing economic output while reducing environmental impact (like CO2 emissions), is technologically possible and being demonstrated in some countries through shifts to cleaner energy, increased efficiency, and technological innovation. The challenge is accelerating this decoupling globally to meet environmental targets, not that any form of growth is impossible or must be environmentally damaging.

Measurement Issues

GDP per capita is a powerful summary statistic, but it was never designed to be a perfect measure of overall human welfare or progress. It omits many things that contribute to wellbeing, such as unpaid work (like childcare or household chores), the value of leisure time, the health of the environment (counting cleaning up pollution as positive GDP) and the distribution of income within a country.

Research attempts to quantify these limitations, showing that welfare can be significantly different from GDP per capita once factors like health, leisure, and inequality are considered

Also the reliability and accuracy of GDP data itself can be questionable, particularly in LMICs with underfunded statistical capacities. This means we sometimes have less reliable data than we assume.

Acknowledging GDP's limitations is essential, but these limitations don't render it useless, especially in contexts where its correlation with fundamental welfare gains is strong. Measurement issues highlight the need for better data collection and alternative or complementary metrics, rather than invalidating the concept of economic progress entirely

Oliver Kim - How Much Should We Trust Developing Country GDP?

African GDP statistics are often highly unreliable due to severe data collection limitations, Zambia's national accounts are prepared by a single person, and Nigeria hasn't conducted a census since 2006

Statistical artifacts can create false economic narratives, as demonstrated by Tanzania's apparent 33% GDP collapse in 1986 (larger than the Great Depression) which was likely just a measurement error when accounting methodologies changed

Major GDP revisions are common, Nigeria's GDP jumped 89% overnight in 2013 when they revised their estimates

Other Concerns

Beyond these major points, growth can be associated with other complex issues:

Animal Welfare

Rising incomes often correlate with increased consumption of animal products, potentially exacerbating the harms of factory farming

Corporate Influence

Powerful economic interests can exert undue influence on government policy, leading to regulations that benefit specific companies/monopolies/oligarchies rather than promoting broader growth

Unforeseen Consequences

Rapid economic transformation can cause social disruption or create new problems that weren't anticipated

Beyond GDP: Alternative Measures of Progress

Given the limitations of GDP, a range of alternative metrics have been suggested. These aim to provide a broader picture of development by incorporating factors that GDP might miss.

Human Development Index (HDI)

Created by the UN Development Programme, the HDI is a composite index that combines life expectancy at birth, years of schooling and Gross National Income (GNI) per capita

Wellbeing Metrics

These approaches try to measure people's subjective experiences of life satisfaction and happiness (through surveys like those used in the World Happiness Report)

Other related metrics, like Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) or Wellbeing-Adjusted Life Years (WALYs) often used in health economics, attempt to quantify the quality as well as the quantity of life

Dashboards of Indicators

Rather than trying to combine everything into a single number, dashboards present a collection of diverse indicators across various domains

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework uses a large set of indicators to track progress across a wide range of development objectives

How development has disappeared from today's 'development' discourse - Video

Ha Joon Chang argues that the modern definition of development has shifted from focusing on the transformation of productive structure to poverty reduction and individual betterment (education, health)

He believes that true development involves upgrading a country's productive capabilities, moving into more difficult industries, and transforming social structures, typically achieved through industrialisation and strategic state intervention

Can We Reliably Promote Growth?

While economists understand the key factors driving long-run economic growth in theory, translating this into predictable, effective interventions to boost a specific country's growth rate has proven difficult in practice.

Identifying reliable levers for growth is complex. Economies are influenced by a vast interplay of internal factors (institutions, geography, culture, history) and external forces (global trade, technology trends, commodity prices).

It appears that transformational, sustained growth spurts are often episodic and seem to emerge from complex, context-specific interactions rather than simple, replicable recipes. This makes finding a single best policy, or even a set of policies guaranteed to work everywhere, probably impossible.

This difficulty presents tractability challenges. Even with good intentions, it's hard for policymakers within a country to reliably engineer growth, let alone for external actors like aid agencies or philanthropies to influence it significantly or predictably. Global forces and deep-seated domestic issues can easily overwhelm well-meaning interventions. New challenges like the potential impact of automation on traditional manufacturing pathways for developing countries add further complexity.

Governments and international bodies continue to pursue common policy approaches aimed at fostering growth. These typically include.

Maintaining macroeconomic stability (low inflation, stable currency)

Implementing structural reforms (improving property rights, liberalising markets, reducing red tape)

Investing in public goods (education, health, infrastructure)

Pursuing more targeted approaches like industrial policy (strategic government support for specific industries), although the effectiveness and risks of this are widely debated and highly context-dependent

The Atlantic - What Really Fueled the ‘East Asian Miracle’?

Conventional wisdom often credits Taiwan's significant land reform in the 1950s with directly boosting agricultural productivity, fueling its later industrial growth

New data analysis suggests this key land redistribution (Phase 3) did not significantly increase farm productivity as widely believed

The reform's positive impacts were more likely driven by complex political factors (like the ruling party securing support and preventing communist movements) and potentially unintended social shifts (like pushing people into manufacturing as small farms became less viable)

This illustrates that historical narratives about development success can be oversimplified, and identifying the true, complex drivers of growth is challenging, highlighting why simple policy recipes based on historical examples may not be reliable or easily replicated elsewhere

Stefan Dercon - Development through Economic Growth

Lack of growth is less about a deficit of technical economic knowledge and more about the underlying political economy and the incentives facing powerful elites

Many poor countries may be in a political equilibrium where elites benefit more from rent-seeking and control of resources than from broad-based growth

Promoting growth effectively requires understanding and potentially shifting these complex political dynamics and elite bargains

Specific intervention areas from this perspective include making 'bad' alternatives (like illicit financial flows or corrupt procurement) more costly and strengthening local political/advisory capacity committed to growth

Lant Pritchett - Rethinking evidence and refocusing on growth in development economics (podcast & article)

Argues development economics overly relies on ‘rigorous’ evidence (like RCTs) and systematic reviews, often ignoring vital local context, leading to misguided policies

Critiques the field's shift from focusing on broad national development and economic growth to narrower poverty alleviation programs

Identifies weak state capability as a crucial yet neglected challenge in development research and practice

Calls for rebalancing development economics to prioritise national development, inclusive growth, and building state capacity, alongside a more balanced and context-aware approach to using evidence

Leverage & Neglected Opportunities

Given the difficulty in reliably promoting national-level growth and the fact that it's a claimed priority for nearly every government and major international institution (World Bank, IMF, etc), one might ask if this is a crowded field for individuals, smaller NGOs, or philanthropies. The answer is likely yes, significant resources and expertise are already dedicated to growth promotion globally.

However, even in a crowded space, there can be potential niches where targeted efforts can still have significant impact. These niches often involve identifying specific bottlenecks, supporting under-resourced areas, or pursuing strategies that larger, more bureaucratic actors might find difficult.

You may find an edge due to the following factors.

Hits-based giving

Willingness to fund uncertain but high-potential ideas that might not fit traditional aid models

Agility and Size

Ability to make smaller, faster grants than large multilaterals

Complementary Role

Supporting civil society, advocacy (particularly on high-income country policies affecting LMICs) or acting as a 'laboratory' to test new approaches

To see how one major philanthropy is thinking about contributing to growth, you could read this summary on why Open Philanthropy have decided to have LMIC growth as one of their focus areas.

Open Philanthropy - Economic Growth in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

OP believes economic growth is central to improving the well-being of the global poor and has decided to invest significantly in this area, despite their own initial skepticism about philanthropic impact

They acknowledge the field is crowded but believe they can find valuable niches due to their willingness to fund uncertain but high-reward opportunities, their agility, and their ability to complement traditional development actors

They are exploring concrete grant areas focused on specific leverage points, such as

Funding high-quality economic policy advice to LMIC governments

Advocating for policy changes (especially in high-income countries) to promote LMIC exports

Supporting efforts to target and curb illicit financial flows

They prioritise finding valuable niches within the crowded field

They recognise the risks and uncertainties involved in promoting growth externally but believe the potential upside for poverty reduction justifies the effort

Specific areas where individuals and smaller organisations might find leverage or contribute include the below.

Economic Policy Advice

Supporting independent, high-quality technical advice to governments in LMICs, especially during reform opportunities or where local capacity is limited (through think tanks or direct advisory roles)

Export Promotion

Advocating for specific policy changes, such as the renewal of trade preferences (like the US's AGOA for African countries) or the reduction of non-tariff barriers that hinder LMIC exports

Targeting Illicit Financial Flows

Supporting investigation and advocacy efforts to combat corruption and capital flight, potentially increasing government resources and deterring extractive behaviour

Improving Data Quality

Working on initiatives to improve the reliability of economic statistics, which is useful for effective policy making and evaluation

Targeted Regulatory Reform

Focusing on specific, identified regulations that pose significant bottlenecks to business or investment

Supporting LMIC Entrepreneurship/Startups

Fostering innovation and job creation from the ground up within LMICs

Focus on Neglected Regions/Approaches

Targeting areas or strategies that are overlooked by major players

It's also useful to consider growth as a by-product. Many effective interventions in other development areas, such as improving health or education, may have positive knock-on effects on economic productivity and human capital, indirectly contributing to long-term growth.

Finding leverage in economic growth means identifying specific problems that are tractable for the actors involved and where the potential impact on generating good, inclusive growth is high, even if success isn't guaranteed.

Careers

For individuals motivated to contribute to fostering economic growth and development, particularly in LMICs, there are various pathways available.

Government & Civil Service

Working within national governments, either in ministries of finance, economy, trade or development agencies (like the FCDO in the UK), or directly within LMIC civil services.

Paths to Impact

High potential for scale and impact by shaping national policy, regulation, and public investment programmes

Direct involvement in national development strategy and resource allocation

Example Roles

Economist or policy advisor roles in the Treasury, Department for Business and Trade, FCDO in the UK

Similar roles in LMIC Ministries of Finance, Planning, Central Banks

National trade negotiators

Pros

Direct influence over significant resources and policy levers

Opportunity to work on systemic issues

Cons

Can be bureaucratic and slow-moving

Susceptible to political shifts and constraints

Potentially lower salaries than private sector

Security challenges in some contexts

Multilateral Institutions

Organisations such as the World Bank, the IMF and regional development banks employ economists and development professionals.

Paths to Impact

Influence global development discourse and standards; inform lending and aid conditionality

Conduct large-scale, multi-country research and analysis

Support macroeconomic stability efforts

Real-world experience in initiatives like Power Africa shows that addressing specific bottlenecks hindering growth (like electricity deficits) requires moving beyond generic fixes towards a transactional approach that mobilises multiple actors

Example Roles

Economist, policy advisor, or programme officer roles at the World Bank, IMF, African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, WTO

Pros

Global reach and significance

Work on complex international issues

Access to vast data and expertise

Opportunities for research and field work

Cons

Can be highly bureaucratic and slow

Potential disconnect from on-the-ground realities

Power dynamics with borrowing countries

Competitive entry

Research, Academia & Think Tanks

Universities and research institutions generate evidence and analysis on the drivers of growth and the effectiveness of different policies, informing development strategies and public discourse.

Paths to Impact

Provide evidence base for policy design and evaluation

Influence expert and public understanding of growth challenges

Training of development professionals

Examples Roles

Academic positions in development economics

Researcher or policy analyst roles at think tanks focused on development (Centre for Global Development, ODI)

Roles at research centres affiliated with universities

Pros

Opportunity to become a leading expert

Contribute to shaping long-term approaches

Cons

Impact can be indirect and take time

Often requires advanced degrees

Highly competitive

Funding can be project-based

Often highly bureaucratic

Private Sector

This includes roles in traditional firms, investment funds, consulting, and directly starting or working for businesses, particularly in LMICs.

Paths to Impact

Directly drive economic activity, create jobs, mobilise capital and build productive capacity

Foster innovation and market solutions

Examples Roles

Consultants advising businesses or governments on emerging markets

Roles in private equity or impact investing funds

Strategy or operations roles in multinational companies operating in LMICs

Founding or working for startups

Pros

Direct contribution to wealth and job creation

Potential for innovation and efficiency

Clear metrics for success (profit, scale)

Higher earning potential

Cons

Profit motive may sometimes conflict with broader development goals

Focus can be narrow

High risk, especially for startups

Philanthropy & NGOs

Organisations focused on non-profit work, grantmaking, and advocacy in global development.

Paths to Impact

Fund specific, targeted interventions and research

Support local civil society and entrepreneurs

Advocate for policy changes (including high-income country policies affecting LMICs)

Experiment with innovative or potentially high-risk approaches

Example Roles

Programme officer or analyst roles at foundations focused on economic growth

Roles in international NGOs focused on improving data quality or reducing illicit financial flows

Pros

Flexibility to fund neglected or risky areas

Mission-driven work with strong values alignment

Ability to work on specific, complex problems often overlooked by larger players

Cons

Resources are limited compared to governments/multilaterals

Challenge of achieving scale

Need for careful evaluation and demonstrating impact

Subject to donor priorities

Questions

Overall Reflection

How has your understanding of the relationship between economic growth and human wellbeing changed?

What surprised you most about the drivers, critiques, or potential leverage points for growth?

Do you feel more or less optimistic about sustained, inclusive growth globally? Why?

Critiques

What's the biggest limitation of GDP per capita as a progress measure?

How significant are environmental constraints on future growth? Can technology fully overcome them?

Is rising inequality an inevitable consequence of growth, or a policy choice?

What are the implications of Poor Numbers for policymaking and our understanding of development?

Interventions & Leverage

Given the difficulty in reliably promoting growth, where should development efforts focus? Specific interventions or broader enabling environments?

How viable are the specific niches identified by OP (policy advice, IFF, export advocacy)? What are the risks?

What are the ethical considerations for external funders (like philanthropies) trying to influence growth policy in LMICs?

Is industrial policy still a viable strategy today?

How much potential lies in pursuing growth as a by-product of other interventions (health, education)?

Trade-offs

How should policymakers balance growth objectives with environmental protection and social equity?

Should LMICs prioritise growth above all else, or focus on wellbeing metrics from the start?

Is it better to fund efforts to measure growth/wellbeing accurately or efforts to directly promote it?

Careers

Which career pathways related to economic growth seem most impactful? Most neglected?

What skills seem most crucial for contributing effectively in this area over the next decade?

Other Resources

Book Review - How Asia Works?

Noah Smith - What ‘How Asia Works?’ got wrong

Probably Good - Economic Growth: An Impact-Focused Overview

Lant Pritchett - The Case for Economic Growth as the Path to Better Human Wellbeing

Unified Growth Theory - Suggests that during most of human existence, technological progress was offset by population growth, and living standards were near subsistence across time

William Easterly - The Elusive Quest for Growth

Tobi Lawson - Ideas Untrapped - Blog looking at growth, with a focus on Africa

EconTalk Podcast - Lant Pritchett on Poverty, Growth, and Experiments

VoxDev - Development Economics Resources

The International Growth Centre

The IGC has tons of resources, including a blog, evidence papers, growth briefs and more

An economics and policy portal focused on growth and development in India

Global Dev - Aiming to connect development research to successful policies

Brookings: Global Economy and Development at Brookings – Research and Commentary

Conversations on Transformation (STEG): Discussions of important new research in structural transformation, growth and economic development

CSAE Research Podcasts: A series of conversations between researchers and collaborators about projects taking place at the Centre for the Study of African Economies

Ideas Untrapped: Tobi Lawson’s podcast offers a platform for debate on ideas that matter for economic growth

Ideas of India: A Mercatur Original Podcast with Shruti Rajagopalan that examines the academic ideas that can propel India forward

Trade Talks (Chad Bown): A podcast about the economics of trade and policy. The “Trade Talks Episode Catalog for Educators” divides these 200 episodes by topic and is a super useful resource.

BREAD-IGC Virtual PhD courses – recordings and slides available at the following links:

VoxLit - overviews of development topics

Dietrich Vollrath - Why Isn’t the Whole World Rich?

Karthik Tadepalli - Growth Theory Reading List

Global development policy can be informed by models that offer helpful diagnostics into the drivers of growth, while growth models can also inform us about how AI progress will affect society

Should Industrial Policy in Developing Countries Conform to Comparative Advantage or Defy it? A Debate Between Justin Lin and Ha-Joon Chang

Victor Kumar looking at the future of fertility rates, population and economic growth

Inflation-adjusted

Total GDP divided by total population

And most of that wealth is tied up in the value of companies rather than liquid assets