This post explores efforts to improve lives globally using evidence. Systematic observation and rigorous testing, which played a key role in the scientific revolution and the development of clinical trials in medicine, has increasingly influenced how we understand and address other global challenges.

In recent decades, global development has seen a shift towards using evidence to inform action. This application has led to the increasing use of methodologies like randomised control trials (RCTs). This shift has generated successes, such as cost-effective interventions to combat infectious diseases, but questions remain about how much evidence can be generalised and how to implement solutions at scale.

Topics

The Evidence Revolution

Science

Medicine

Randomised Control Trials

Critiques of RCTs (and Impact Evaluation)

Evolution of the Field

Practical Implementation Challenges

Global Health

The Current Global Health Landscape

Key Global Health Areas

Global Health Spending

Career Pathways in Global Health

The Evidence Revolution

Science

The pursuit of evidence as a cornerstone of understanding and progress has deep historical roots. The scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries marked a fundamental shift away from reliance on tradition and authority towards systematic observation, experimentation and the formulation of testable hypotheses. It hinged on the earlier invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century. This allowed scholarly works to be more widely read and enabled people to build upon previous knowledge, rather than starting from scratch. This acceleration in knowledge dissemination paved the way for evidence-based thinking.

Key moments:

1543 - Copernicus's heliocentric model challenged the long-held geocentric view. This was a shift in perspective, placing the Sun, rather than the Earth, at the center of the solar system and questioning humanity's central place in the universe

1610 - Galileo used the newly invented telescope to make astronomical observations, discovering the moons of Jupiter, which provided evidence supporting Copernicus and further undermining the accepted understanding of the cosmos. This demonstrated that celestial bodies could orbit something other than the Earth, weakening the view that everything revolved around our planet

Francis Bacon emphasised inductive reasoning and careful observation. His ideas about systematic experimentation and collaborative research helped lead to the establishment of the Royal Society of London (after his death), which formalised scientific investigation by providing a platform for sharing findings, replicating experiments and engaging in peer review

1687 - Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation, providing a mathematical framework for explaining a wide range of physical phenomena. They offered a unified explanation for both terrestrial and celestial motion, establishing the foundation for classical physics and enabling future technological advancements

These intellectual transformations laid the groundwork for evidence-based approaches in other domains, including a gradual evolution within academia. While the scientific revolution was driven by individual scientists, scientific societies and wealthy patrons largely outside the traditional university system1, the growing prestige and practical successes eventually spurred universities to incorporate scientific disciplines. Over time, universities increasingly adopted peer review and empirical methodologies as key parts of academic inquiry.

Medicine

Building upon the foundations laid by the Scientific Revolution, the medical field underwent its own transformative period. It saw a shift from relying on traditional remedies and anecdotal observations towards a scientific understanding of disease and treatment. As diseases were increasingly understood through a biological lens with the advent of germ theory, the need for evaluation of medical interventions became increasingly apparent.

Development of Vaccines: Edward Jenner's work with cowpox vaccination in 1796 demonstrated the possibility of preventing infectious diseases by stimulating the immune system with a weaker version of the disease

Germ Theory of Disease: The work of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch established that many diseases are caused by specific microorganisms. This breakthrough revolutionised sanitation practices and laid the foundation for vaccines and antibiotics

Antiseptic treatments: In 1865 Joseph Lister's application of carbolic acid to sterilise surgical instruments and wounds dramatically reduced infections from operations

Public Health Interventions: The implementation of clean water systems, improved sanitation, and other public health measures significantly reduced mortality from infectious diseases

John Snow is credited as a founder of modern epidemiology for studying the Broad Street cholera outbreak and his hypothesis that germ-contaminated water was the cause, rather than something in the air called ‘miasma’

The Metropolis Water Act of 1852 introduced the regulation of the water supply companies in London, including minimum standards of water quality for the first time

The advances in understanding the causes of disease, coupled with a growing emphasis on systematic evaluation of treatments, transformed the practice of medicine.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, statistical methods began to be applied to medical data, allowing researchers to identify correlations and trends

In the mid-20th century, cohort studies and case-control studies became more widely used, enabling researchers to investigate the relationship between risk factors and disease outcomes

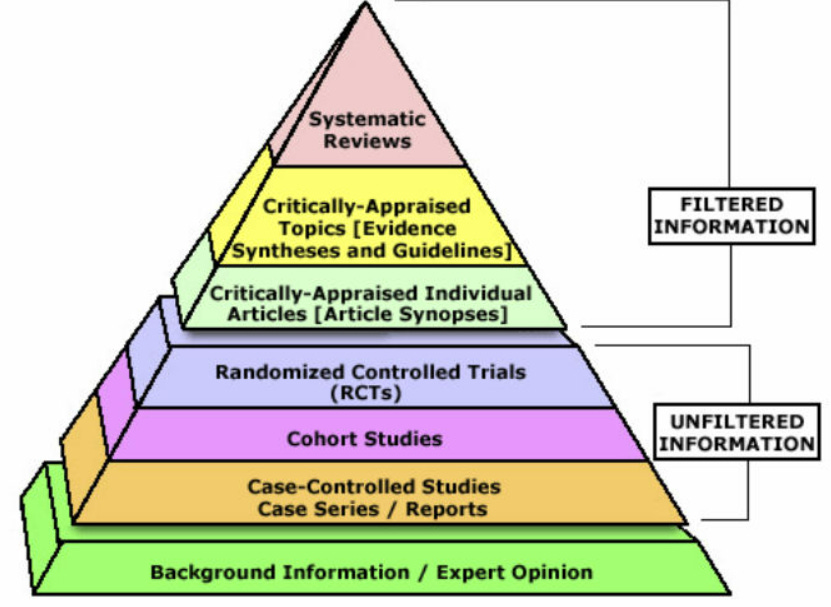

By the 1980s, the importance of synthesising evidence from multiple studies was increasingly recognised, leading to the development and widespread adoption of meta-analyses and systematic reviews as key components of evidence-based practice

Increasingly, cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) was adopted to evaluate the relative value of different interventions, informing resource allocation decisions by comparing costs to health outcomes achieved. CEA often uses standardised metrics like Quality-Adjusted Life Years2, Disability-Adjusted Life Years3, and Well-being Adjusted Life Years4 to quantify the health and well-being benefits of interventions, allowing for comparisons across different diseases and programs.

The data needed to perform rigorous CEAs often relies on well-designed studies, and one of the key tools that was developed and used in multiple fields to generate this evidence is the randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Randomised Control Trials

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) is an experiment designed to control for factors outside of direct experimental control. In an RCT, participants are randomly allocated to different treatment groups. This random allocation helps to ensure that the groups are statistically comparable, even for characteristics that researchers haven't identified or cannot directly manage. When well-designed, properly conducted and involving a sufficient number of participants, an RCT can provide a robust comparison of the treatments being studied, mitigating the influence of confounding factors.

The history of RCTs: scurvy, poets and beer (4 minutes)

1747 - Naval surgeon James Lind compared different treatments for scurvy among six pairs of sailors and he was trying to make sure that the men in the different treatments were as similar as possible5

1884 - Psychology researcher Charles Pierce randomised the order in which subjects received different weights to test their perception of small differences

1920s - The Rothamsted Agricultural Research Station conducted randomised field experiments in agriculture, laying groundwork for statistical analysis in research

1927 Shaffer and other researchers randomly assigned individuals to groups in psychology experiments

1950s - Large-scale RCTs assessed the effectiveness of the polio vaccine, contributing to its widespread adoption

1960s - Heather Ross conducted a field experiment that examined the impacts of negative income tax, representing early use of RCTs in economics

1974 - One of the first development economics experiments investigated teaching mathematics over the radio in primary schools

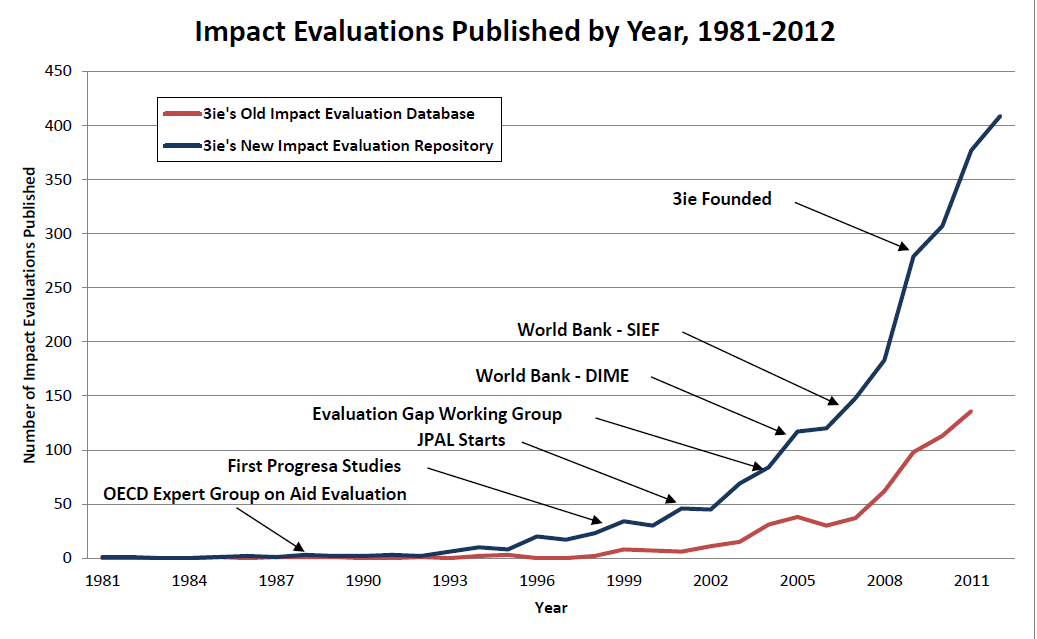

In 2004 the Center for Global Development convened the Evaluation Gap Working Group. The group was asked to investigate why rigorous impact evaluations of social development programs, whether financed directly by governments or supported by international aid were relatively rare.

3ie - Trends in impact evaluation: Did we ever learn? (3 minutes)

Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo's 'Poor Economics' book released in 2011 advocated for an increasingly evidence-based approach to tackling global poverty, challenging grand theories and market-based solutions. The book proposed understanding the decisions and circumstances of the poor through rigorous RCTs and argued that small, well-targeted interventions could lead to significant progress.

Following the growing recognition of a desire for rigorous evidence in global development, a range of influential organisations emerged or shifted their priorities. The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) spearheaded the movement by focusing on generating research through hundreds of RCTs globally, partnering with implementing organisations to conduct real-world experiments and influencing billions in development spending through its findings.

Funders like USAID and the Gates Foundation, traditionally focused on large-scale interventions, began allocating significant resources to RCTs and other rigorous evaluations.

Rachel Glennerster - When do innovation and evidence change lives? (5 minutes)

This shift was driven by a desire for greater accountability and a feeling that traditional development approaches had yielded limited or uncertain results.

However, the increased emphasis on RCTs also sparked debates about the limitations of this methodology.

Critiques of RCTs (and impact evaluation generally)

The use of RCTs and broader impact evaluation tools in global development are not without detractors. A range of concerns have been raised, including questions about generalisability, scaling effectiveness, ethical considerations and whether micro-level interventions can address macro development challenges.

Stephanie Wykstra - It’s difficult to test whether poverty relief actually works. Do randomised controlled trials provide a scientific measure? (8 minutes)

Limited Generalisability

RCT results may not easily translate to different contexts, undermining their broad applicability for policy decisions. For example, from the above article, successful teacher hiring programs in Kenya failed to replicate when implemented with government teachers

David Roodman - The Smartest RCT Critic

Suggests that while RCTs excel at establishing internal validity within a study, the subsequent process of applying those findings externally still requires assumptions about population similarities, mirroring the challenges RCTs aim to overcome internally

Eva Vivalt - What do 600 papers on 20 types of interventions tell us about how much impact evaluations generalise?

Impact evaluations of the same intervention can produce widely different results across contexts, with the typical difference between studies being about 50% of the average effect

The Micro vs. Macro Debate

While RCTs might demonstrate the effectiveness of interventions like distributing bed nets, they don't address underlying issues such as trade policy, leading to questions about whether RCTs, often focusing on micro-level interventions, address root drivers of poverty compared to broader policy changes

Research Vulnerabilities

Publication bias and selective reporting can skew the results of even well-designed RCTs

For example, from the above article by Wykstra, when the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute required pre-registration of studies, this dramatically reduced positive results being reported. While this issue affects non-RCTs as well, it demonstrates how scientific processes can undermine methodological rigour

Practical Implementation Challenges

Scaling Challenges

Scaling successful interventions beyond controlled trials introduces more challenges:

Complexity

Scaling interventions beyond pilot programs introduces bigger logistic, management and coordination challenges

Costs

Implementation costs often don't scale linearly, with diseconomies of scale emerging in complex environments. Initial cost-effectiveness calculations from small trials can underestimate large-scale implementation expenses

Staff motivation and quality

Interventions initially implemented by small teams of highly motivated researchers often struggle when scaled through government systems or larger bureaucracies. The attention to detail and problem-solving capabilities present in pilot phases may not translate to larger workforces operating under different incentive structures and varying levels of commitment

Political economy factors

Local power structures can significantly impact implementation. Successful pilots may falter when confronted with bureaucratic resistance, competing priorities or corruption

Research initiatives like the Yale Research Initiative on Innovation and Scale (Y-RISE) are investigating these challenges to understand how to preserve impact while navigating the transition from controlled studies to real-world implementation.

Resource Constraints

RCTs are typically expensive and time-consuming to implement properly, which can limit their feasibility in resource-constrained settings. The high costs of data collection, analysis and monitoring can divert resources from program implementation, raising questions about opportunity costs in development spending.

Methodological Limitations

Hawthorne Effect

Subjects behaving differently simply because they know they're being studied can artificially inflate intervention effects. For example, households that receive regular monitoring visits as part of an RCT may change their behaviour in ways that wouldn't occur in a scaled program without such intensive observation.

Time Horizons

RCTs typically measure short-term effects, but scaled interventions may produce different outcomes over longer timeframes, creating challenges for predicting long-term impact. Many important development outcomes unfold over years or decades, beyond the typical timeframe of an RCT.

This is especially relevant in countries that are changing economically, demographically, culturally in a short amount of time.

Evolution of the Field

While RCTs in development economics face legitimate criticisms, practitioners have evolved their methods to address these critiques.

Tim Ogden - RCTs in Development Economics, Their Critics and Their Evolution

The fundamental disagreements about RCTs stem from different theories of change regarding:

The value of small vs. big interventions

Technocratic expertise vs. local knowledge

The role of individuals vs. institutions in development

Using the ‘Hype Cycle’ framework, Ogden argues that RCTs have matured past inflated expectations and are now in a more productive ‘slope of enlightenment’ phase, with practitioners implementing more sophisticated designs, addressing causal mechanisms, and building institutions to support evidence-based policymaking.

Conclusion

While RCTs have made valuable contributions to development economics and policy, understanding their limitations is critical for appropriate application. The critiques outlined above highlight potential value in methodological pluralism. Rather than relying exclusively on RCTs, the field is moving toward a more nuanced understanding of when they are most useful and how they can be complemented by other research approaches.

Building on this broader understanding of evaluation methodologies, it's useful to examine the progress and ongoing challenges in specific areas of global development. One of the most fundamental of these is global health, where significant strides have been made in improving life expectancy and reducing mortality, but substantial issues persist.

Global Health

Global health is a field focused on improving health for all people worldwide, often with particular focus on improving health outcomes for the world's poorest and most vulnerable populations. There can be challenges that transcend national boundaries and require collective international action but it also covers countries improving their own health systems. This field has been significantly shaped by the evidence revolution, with better measurement and evaluation methods transforming how we understand and address health challenges globally.

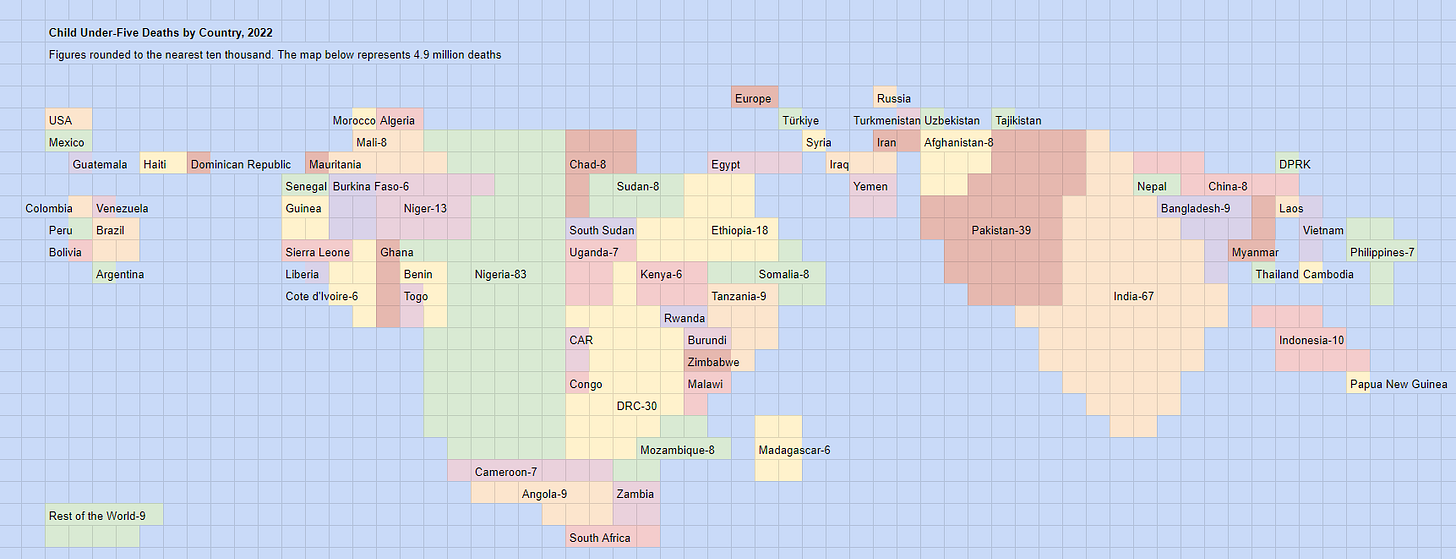

Over recent centuries, we've witnessed remarkable progress in health outcomes, with significant increases in life expectancy and reductions in child and maternal mortality. While lower-income countries have made considerable strides, substantial gaps remain, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where many still lack access to basic healthcare services.

The Current Global Health Landscape

Understanding the global distribution of disease and mortality offers useful context for seeing how everything fits together.

Our World in Data - An overview of our research on global health (10 minutes)

Several key trends:

Declining mortality rates: Child mortality rates have decreased significantly worldwide but remain much higher in low-income countries

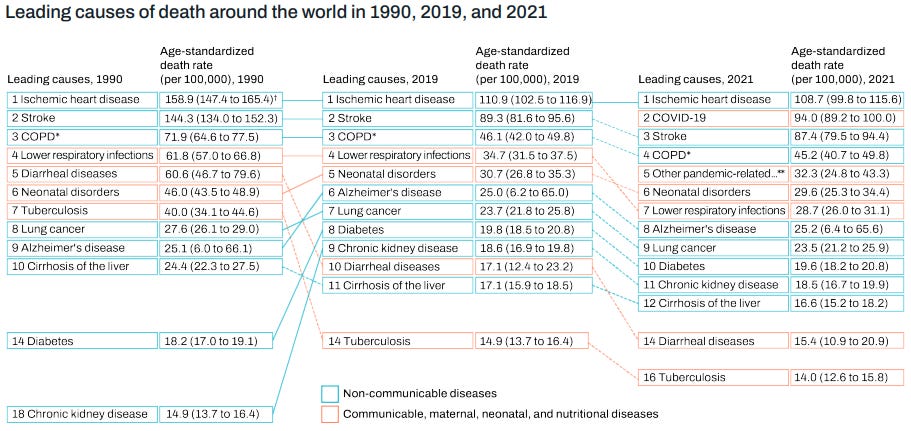

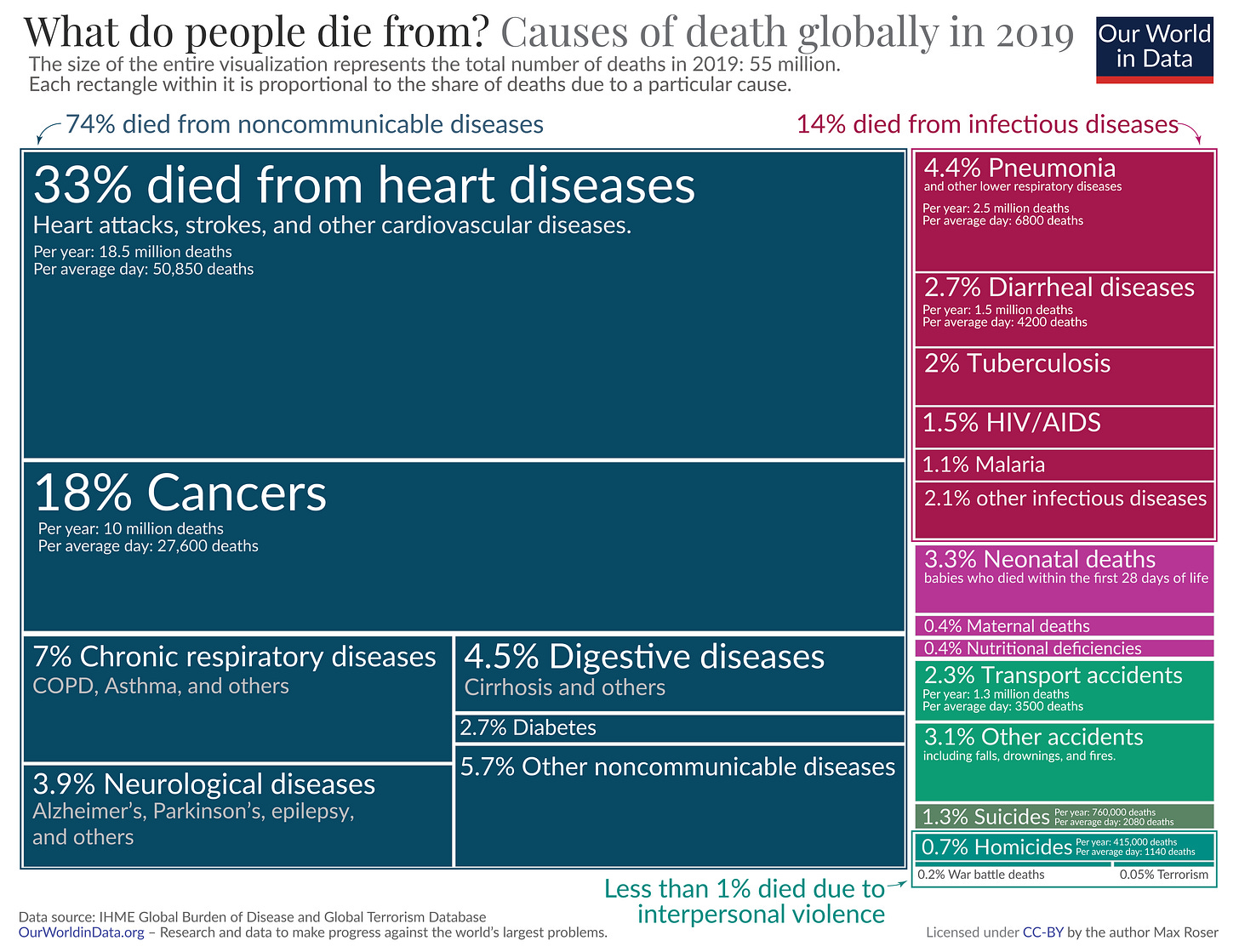

Shifting disease burden: Non-communicable diseases like heart disease and diabetes now account for approximately 74% of global deaths

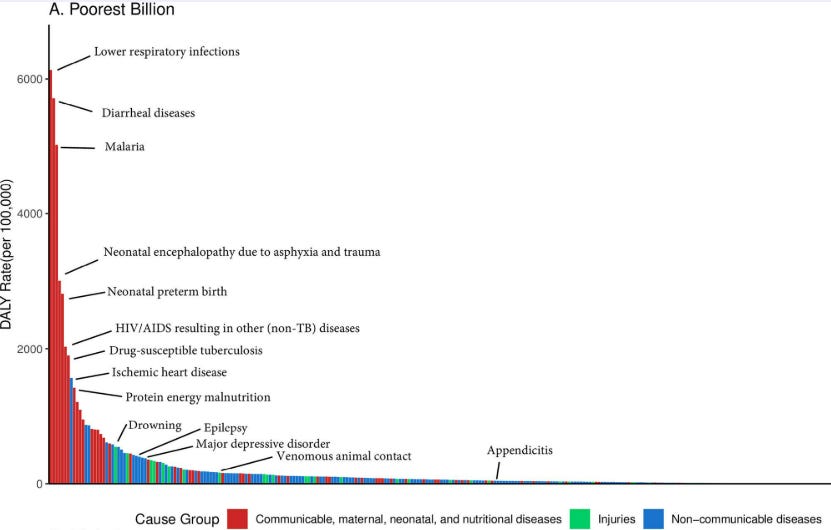

Persistent issues: Health challenges disproportionately affect certain regions and populations, with the poorest billion people bearing a much higher burden of preventable disease

Global Mortality Trends

The leading causes of death worldwide have evolved significantly between 1990 and 2021. While communicable diseases remain prominent in low-income settings, non-communicable diseases now dominate global mortality statistics. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has further altered this landscape.

Health Outcome Disparities

Despite progress, the burden of disease is not evenly distributed:

Communicable diseases continue to disproportionately affect the poorest populations

Life expectancy in low-income countries remains significantly lower than in high-income countries

Within countries, the poorest and most vulnerable often face the greatest health challenges

Key Global Health Areas

Global health efforts are typically organised into areas addressing specific categories of disease and their influencing factors. The following represent major domains in contemporary global health practice:

NCDs, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and chronic respiratory conditions, now account for the majority of global deaths (around 74% in 2019)

Their prevalence is rapidly increasing in lower-middle income countries (LMICs) where healthcare systems are often less equipped to manage chronic conditions

Infectious Diseases/Communicable Disease

Major persistent epidemics (HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis)

Emerging threats (Ebola, COVID-19, "Disease X"6)

Antimicrobial resistance

Neglected tropical diseases affecting billions worldwide cumulatively

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH)

Approximately 2 billion people globally lack access to safely managed drinking water, while 3.6 billion lack adequate sanitation. These deficiencies contribute to diarrhoeal diseases that:

Cause ~830,000 deaths annually

Remain the second leading cause of death in children under five years

Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (MNCH)

This area addresses pregnancy-related health needs, childhood illnesses and nutrition affecting ~130 million births annually worldwide. Despite improvements, each year:

Approximately 295,000 women die during pregnancy and childbirth

Around 5 million children die under the age of 5

Global nutrition challenges present in multiple forms:

Approximately 828 million people faced hunger in 2021

An estimated 149 million children under five suffer from stunting and 45 million from wasting

Over 2 billion adults are overweight or obese, highlighting the "double burden" of malnutrition globally

Mental Health and Substance Use

Mental health represents a growing global health priority:

In 2019, an estimated 970 million people worldwide were living with a mental disorder, with depression and anxiety as the top two diagnosed conditions

Mental health conditions account for approximately 14% of the global burden of disease

Suicide claims nearly 800,000 lives annually

Significant challenges persist in accurate diagnosis, with large variation between countries

Health systems comprise the infrastructure, workforce, financing, innovation and governance that underpin health interventions. Systems worldwide vary greatly in their structures. Most health systems include:

Primary healthcare and public health measures: The foundation of most effective health systems

Varying governance structures: Some systems are decentralised with multiple stakeholders, while others are centrally coordinated

Multiple actors: Including government entities, private providers, charitable foundations, religious institutions and professional medical associations

The strength and design of health systems significantly impact a country's ability to deliver effective interventions and respond to health challenges

Environmental factors significantly impact global health:

Air pollution is associated with approximately 7 million premature deaths annually

Over 90% of the world's population breathes air that exceeds WHO guideline limits

Chemical exposures, unsafe water, and climate change impacts contribute significantly to global disease burden

Lead pollution contributes to 1% of the global disease burden

Injury Prevention and Trauma Care

Injuries represent a substantial but often overlooked health challenge:

4.4 million lives were lost due to injury in 2019 (8% of all deaths)

Road traffic accidents (1.3 million deaths), violence, falls and burns result in millions of fatalities and injuries annually

Injuries are the leading cause of death for people aged 5-29 years worldwide

93% of fatal road traffic injuries occur in LMICs

Sexual and Reproductive Health

This domain encompasses family planning, STI prevention/treatment and sexual health services:

Approximately 218 million women have an unmet need for modern contraception

Over 38 million people live with HIV globally

An estimated 357 million new cases of four curable STIs occur annually

There are many more areas, sub-fields and cross-cutting topics related to global health, but the above are some of the main fields. They highlight the wide range of challenges and possible interventions. Beyond identifying these areas, many practitioners and researchers also examine the effectiveness of different approaches. Understanding what works, and to what degree, can inform decisions about prioritising actions and allocating resources.

Why focus on effectiveness in global health?

Why might practitioners and researchers pay attention to the effectiveness of different interventions? In a world with limited resources for addressing numerous health challenges, understanding which approaches deliver the best outcomes can be valuable. This consideration becomes particularly relevant in resource-constrained settings where healthcare budgets must stretch to cover many competing priorities.

Toby Ord - The Moral Imperative toward Cost-Effectiveness in Global Health (10 minutes)

The difference between the most and least effective health interventions can be massive, for example, within HIV/AIDS interventions, the least effective intervention produces less than 0.1% of the value of the most effective

Historical examples like smallpox eradication (costing approximately $15 per life saved while also saving billions in healthcare costs) demonstrate the dramatic variance in intervention outcomes

Limitations and Complexities of Effectiveness Analysis

While examining effectiveness can be informative, it has limitations. The PEPFAR case study (President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) provides an instructive example.

Justin Sandefur - PEPFAR and the Costs of Cost-Benefit Analysis (5 minutes)

Initially, some economic analyses suggested prevention would be more cost-effective than treatment for HIV/AIDS

However, PEPFAR ultimately saved millions of lives as drug prices fell dramatically from $100,000 to $300 per patient annually

The economists' initial assessments missed two key factors: the potential for rapid price reductions through generic production and the possibility that new funding could expand the total resources available rather than simply redirecting existing budgets

Global Health Spending

Understanding how health systems are financed is fundamental to addressing global health challenges. The allocation of financial resources for health, directly impacts who can access healthcare, which services are available and the health outcomes of populations.

Knowledge of global health financing context can help us make more informed decisions when choosing careers, directing donations or advocating for policy changes.

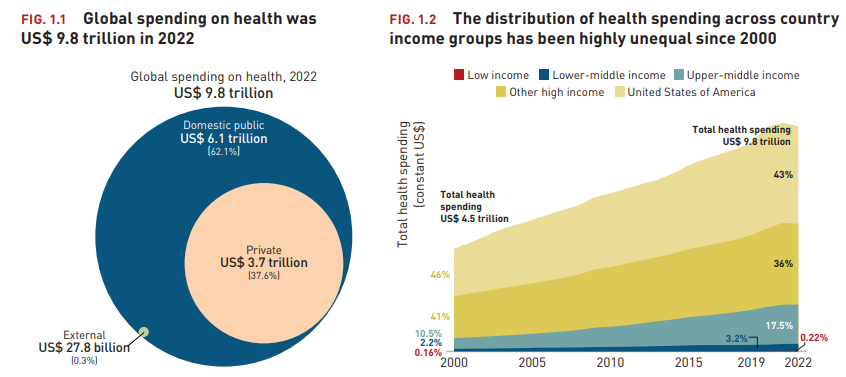

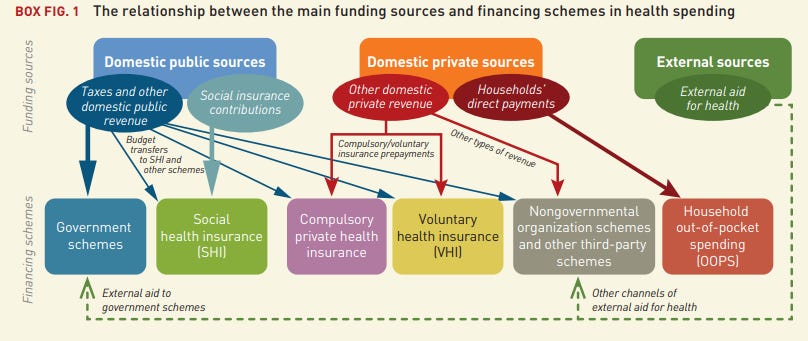

Total global spending on health reached $9.8 trillion in 2022 (about 10% of global GDP), more than doubling from $4.5 trillion in 2000. Health spending is made up of government expenditure, out-of-pocket payments (people paying for their own care), and sources such as voluntary health insurance, employer-provided health programs and activities by NGOs.

High-income countries account for 79% of health spending (US alone is 43%)

Domestic public spending accounts for 62%, while private spending represents 37.6% ($3.7 trillion)

External aid constitutes 0.3% ($27.8 billion) of global health expenditure, although this can be a larger proportion of spending in the poorest countries

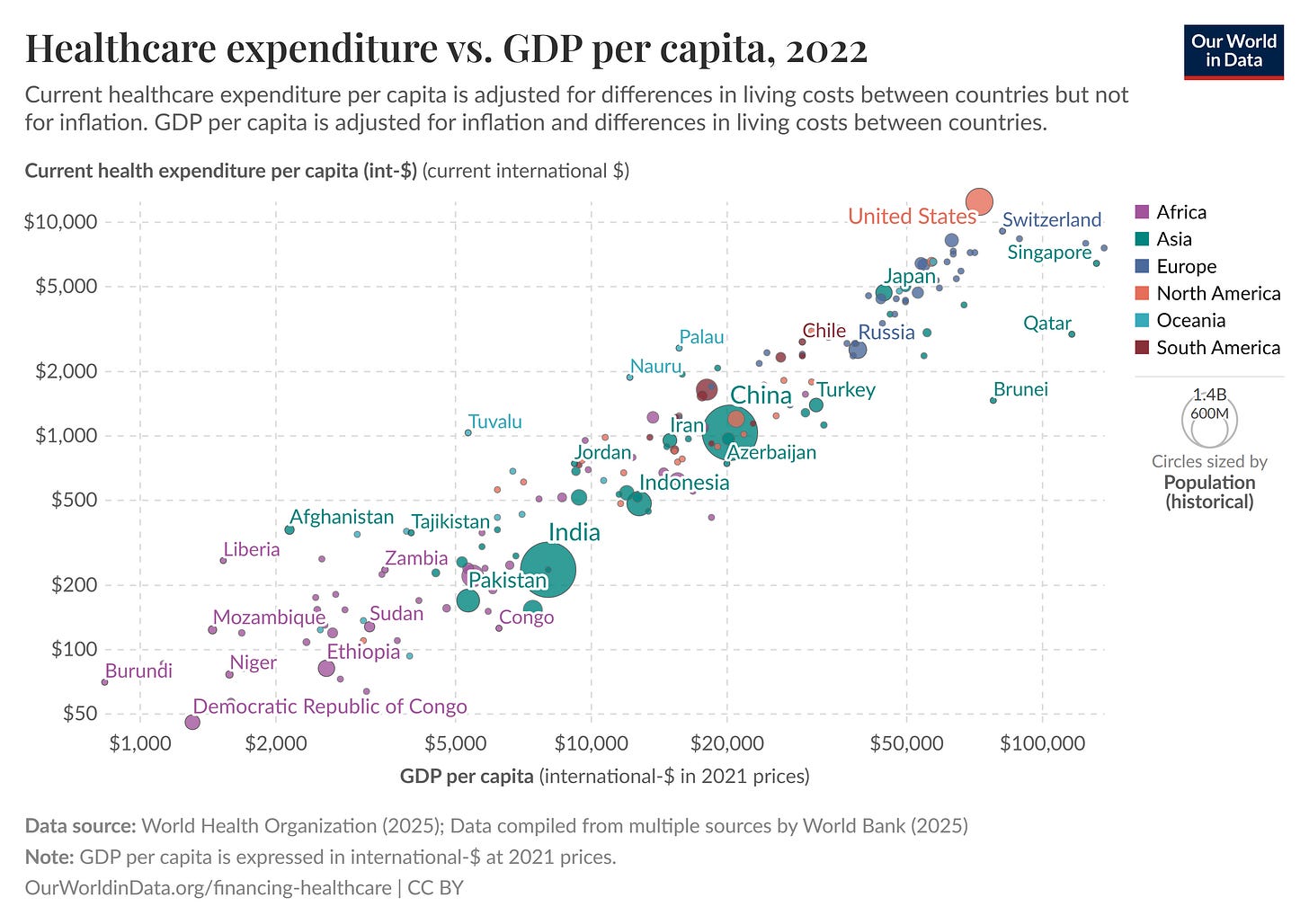

Our World in Data - Healthcare Spending (10 minutes)

A comprehensive overview of global healthcare financing trends

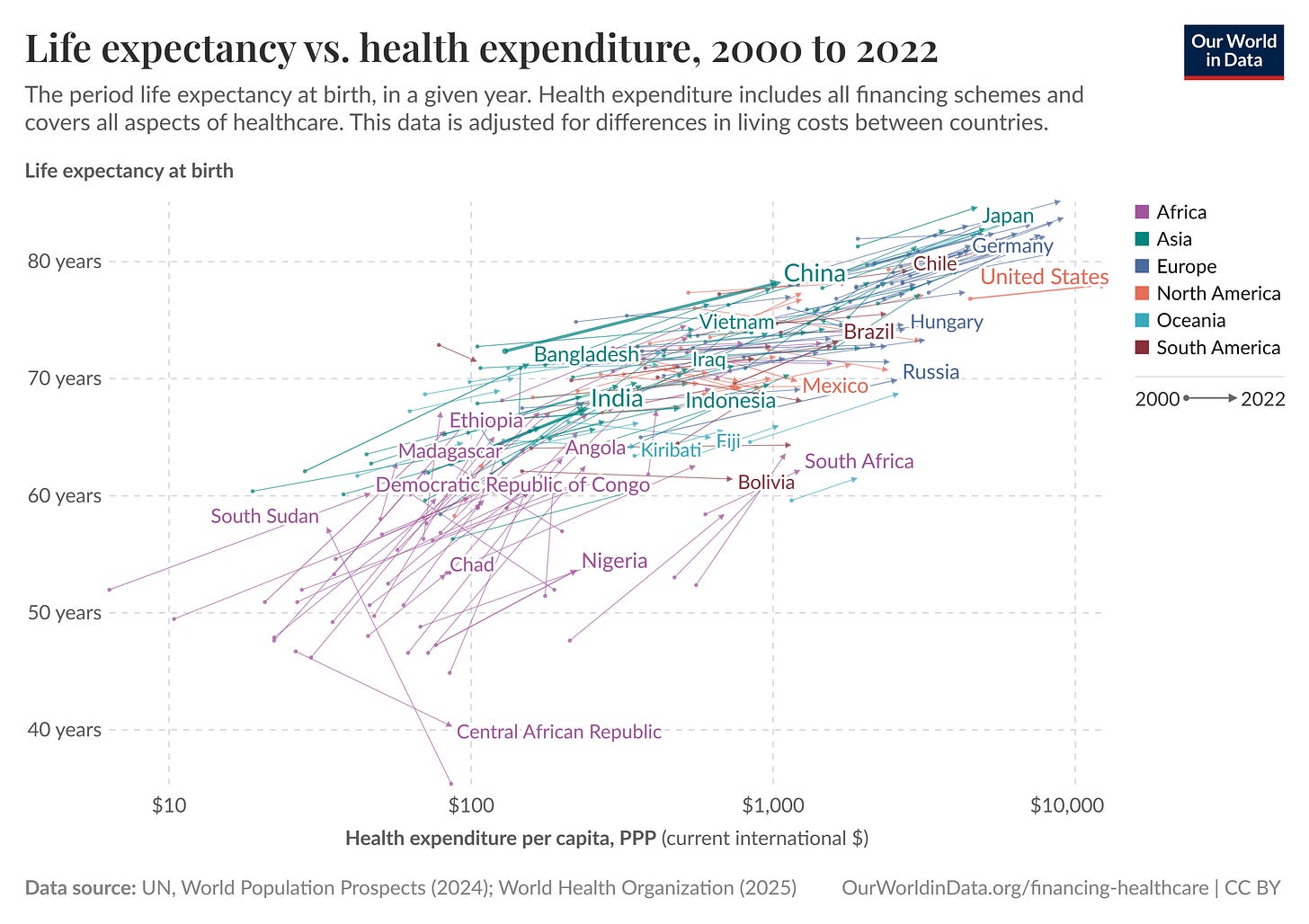

Relationship Between Spending and Health Outcomes

Healthcare spending per capita shows a positive correlation with life expectancy, though with diminishing returns as spending increases. This relationship is particularly evident when comparing countries across income groups:

Low-income countries typically see significant gains in life expectancy with relatively modest increases in healthcare spending ($43 per capita)

Middle-income countries experience continued improvements but at a decreasing rate per additional dollar spent ($132-$540 per capita)

High-income countries show minimal marginal improvements despite substantially higher spending ($3,731 per capita)

This pattern suggests that initial investments in healthcare systems yield the greatest returns, particularly for basic interventions like vaccinations, maternal care and infectious disease control.

National Income and Health Investment

National income remains the strongest predictor of healthcare spending. This relationship is causal rather than merely correlational, as countries become wealthier, they allocate more resources to health through both public and private channels.

Sources of Healthcare Funding

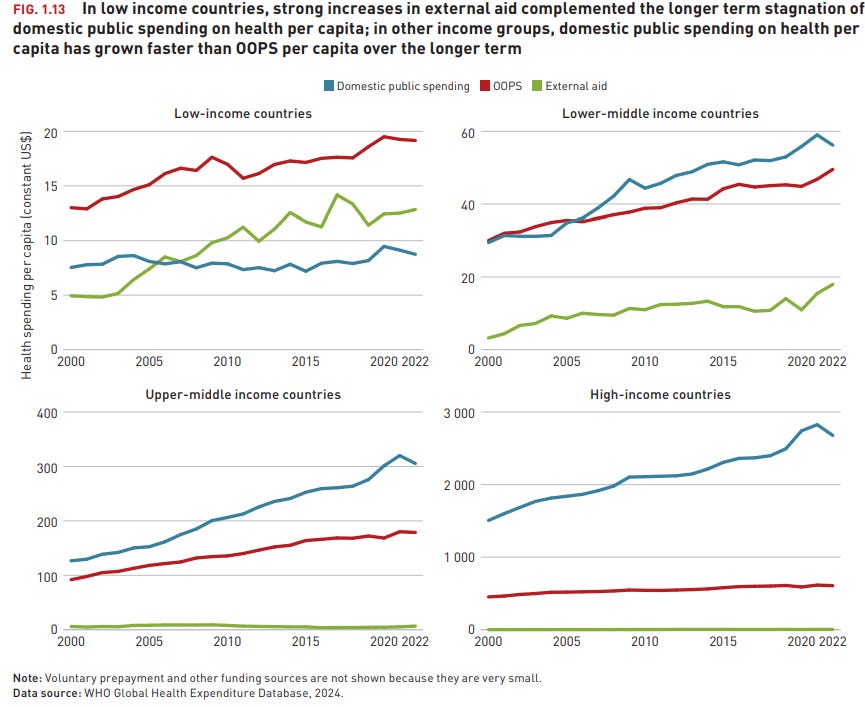

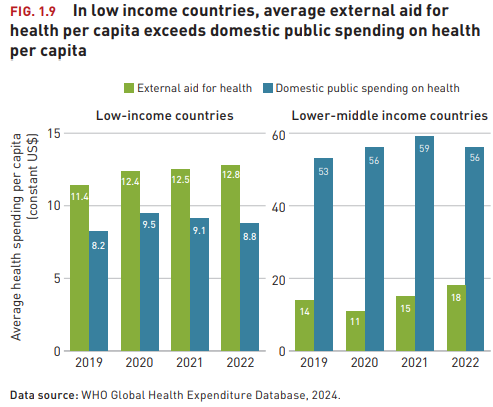

Domestic vs External Funding

Healthcare systems are primarily funded through domestic sources (government and private sector (out of pocket spending)). However, the dependency on external donor funding varies significantly by economic development. This creates particular vulnerability for low-income countries, whose health systems may experience disruption when donor priorities shift.

Development Assistance

Since the establishment of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000, development assistance for health has increased significantly, especially for targeted areas like child mortality, maternal health, malaria and tuberculosis

Between 2000 and 2019, the share of health spending channelled through government schemes (mainly health budgets) and compulsory health insurance (mainly social health insurance) increased steadily except in low-income countries where it remained mostly unchanged.

In the poorest countries (GDP per capita below $500), donor funding constitutes ~45% of health expenditure

As countries develop economically, this external reliance steadily declines: to 34% for those with GDP per capita up to $1000

Below 25% for nations up to $3000

Once countries exceed $3000 GDP per capita, external health funding typically represents less than 5% of total health expenditure

Health Financing Mechanisms

Healthcare financing comes through several key sources including public, private, out-of-pocket spending (OOPS) and external aid.

Public Financing

Government financing through general taxation or specific health taxes is the main funding for most healthcare systems. Countries with higher tax-to-GDP ratios generally achieve better health coverage with lower out-of-pocket expenses

Health Insurance

Health insurance mechanisms spread financial risk across populations, but differ in how they're funded, who's covered and who manages them.

Government expenditure (tax-funded systems): Funded through general taxation, covers all citizens regardless of contribution, and is directly managed by government. Examples include the UK's NHS and Canada's Medicare

Social Health Insurance (SHI): Typically mandatory, funded through dedicated payroll contributions (not general taxes), managed by quasi-public agencies or funds and traditionally linked to employment status. Examples include Germany's sickness funds and Japan's system. The number of countries with SHI schemes has risen significantly, particularly among middle-income countries

Private Health Insurance (PHI): Private health insurance exists in most countries but varies greatly in its role and market share.

Supplementary: Covers services beyond public provision (France, Canada, Australia)

Duplicate: Offers faster access or provider choice alongside public systems (UK, Spain, Australia)

Primary: Serves as main coverage for certain populations, sometimes being mandatory for all citizens (US, Switzerland, Netherlands)

Out-of-Pocket Expenditure

Direct payment at the point of service remains a significant financing mechanism in many low and middle-income countries. High out-of-pocket spending is associated with:

Catastrophic health expenditure (defined as spending >10% of household income on health)

Delayed or foregone care

The WHO estimates that approximately 930 million people globally spend at least 10% of their household budget on healthcare.

While the number of countries with out-of-pocket spending (OOPS) as the main health financing mechanism has declined since 2000, it remained the main financing scheme in 30 low and LMICs as of 2022. In 20 of these countries, OOPS accounted for more than half of total health spending.

Innovative Financing

As traditional funding sources face constraints, new financing mechanisms are increasingly being suggested.

Sin taxes on tobacco, alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages, which both generate revenue and reduce consumption of harmful products

Impact bonds that link investor returns to measurable health outcomes

Blended finance mechanisms combining public, philanthropic and private capital

Debt swaps for health, where external debt is forgiven in exchange for domestic health investments

The Future of Healthcare Financing

Ageing populations globally will drive increased healthcare costs for non-communicable diseases and changing dependency ratios affecting social insurance mechanisms

New health technologies present potential cost savings through telemedicine and digital health but also increased pressure to finance more expensive newer treatments and diagnostics

New technologies in general could lead to faster economic growth, safer workplaces, cleaner energy, safer roads, etc leading to lower health demands

Changing climates could impact temperature related deaths, crop success and migration, impacting health systems

Changes in foreign aid could impact what does and doesn’t get funded in lower income countries and lead to shifting prioritisation by governments

Careers in Global Health: Making an Evidence-Based Impact

For those interested in improving global health outcomes, several career pathways offer opportunities to make a meaningful impact. However, not all paths will be equally impactful (even with a specific field or a specific organisation there is wide variation in the amount of change you can make). To make the biggest difference, it's crucial to think strategically about where your skills and interests can best be leveraged to address these problems.

Multilateral & Intergovernmental Organisations

These organisations set global health norms, coordinate international responses and provide technical guidance. They usually offer more stable careers with wide-reaching influence, though bureaucratic constraints can limit agility.

Organisations:

World Health Organisation (WHO)

United Nations agencies (UNICEF, UNFPA, UNAIDS)

Global funds (Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, GAVI)

World Bank and regional development banks

Key Roles:

Policy advisor/Technical specialist: Shapes global health policies and provides subject-matter expertise

Epidemiologist/Biostatistician: Analyses disease patterns and study designs to inform response strategies

Health economist: Evaluates cost-effectiveness of interventions and advises on resource allocation

Programme coordinator/manager: Manages implementation of health initiatives across multiple countries

Government & Civil Service

Government institutions direct health system governance and service delivery within countries. The promise of influencing health systems at a national or international level is a major draw. Success here relies on navigating significant political constraints. It often requires exceptional advocacy and communication skills to navigate the landscape, as well as building strong networks to effectively advocate for evidence-based policies. Their is job insecurity inherent in politically sensitive roles, with a high chance of being out of power for several years at a time, vs having less power but more constant access as a civil servant/policy advocate.

Organisations:

Ministry/Department of Health

Public health institutes

Local/municipal health departments

Foreign affairs departments

Aid departments (for richer countries)

Key Roles:

Civil Service - Probably Good on Civil Service Careers in LMICs

Political roles: Directly shapes health legislation and budget allocation, though success relies on navigating significant political constraints

Policy advisor, programme director

Clinical & public health practice

The frontline workforce delivering healthcare services and public health interventions. While clinical roles are abundant globally, there's significant maldistribution, with shortages in rural and low-income settings, particularly for specialists. A higher change of seeing direct patient impact and more meaningful work but potentially limited systemic impact. To address this, you could focus on areas with the greatest unmet need and roles that allow you to mentor other healthcare professionals, or eventually move into health policy, amplifying your impact.

Global health clinician: physician, nurse, allied health professional

Community health coordinator, health education lead

Specialists in: disease control, nutrition, child health, mental health, etc

Non-Governmental Organisations

NGOs implement programmes and advocate for change. They offer a range of entry points but often face funding instability and variable career progression paths as well a wide variation in impact even if they are successful in their aims.

Organisations:

International NGOs (MSF, Partners in Health, PATH)

Disease-specific organisations

Community/Regional-based organisations, advocacy groups

Key Roles:

Programme manager/Field coordinator: Oversees implementation of health interventions, balancing evidence-based approaches with adaptation to local contexts

Technical advisor, monitoring & evaluation specialist, fundraising, communications

Research & Academic Institutions

These institutions generate and synthesise evidence to inform policy and practice. Academic careers are often highly competitive for entry and advancement but provide opportunities for specialised expertise development.

The strength lies in potential through rigorous research and data analysis. However it relies on others translating research into action. To mitigate this, prioritise focusing on research areas with high potential for scalable impact (e.g., cost-effectiveness of interventions, implementation science, evidence synthesis). Actively seek opportunities to collaborate with policymakers to ensure findings are translated into real-world policies.

Organisations:

Universities

Teaching hospitals

Research institutes

Public health schools

Policy think tanks, evidence synthesis organisations

Philanthropy & Funding Organisations

These entities set priorities through resource allocation decisions. Though smaller in number, these roles have outsized influence on the field's direction, usually with good working conditions but limited entry points.

Organisations:

Private foundations (Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust)

Corporate foundations

Donor advised funds

Venture philanthropy organisations

Key Roles:

Grantmaker/Program officer: Evaluates proposals and makes funding decisions that shape global health priorities

Impact investment analyst, Strategic advisor

Operations roles

Private Sector

The private sector develops products, technologies and services that address health needs. There's increasing engagement in global health with diverse entry points and often stronger resources than public/non-profit sectors.

Organisations:

Pharmaceutical & medical technology companies

Digital health companies, health consulting firms, analytics

Impact investors

Sanitation and clean water technology providers

Innovation & Entrepreneurship

This cross-cutting category spans multiple sectors, driving new technologies and approaches to overcome global health challenges. It's an area with high potential for disruptive solutions, though with higher failure rates balanced by potentially outsized impact.

Organisations:

Start-ups

Innovation labs

Incubators and accelerators

Social enterprises

Key Roles:

Entrepreneur (Social/Charity): Develops innovative business models or non-profit organisations addressing health gaps.

Innovation lab director/Incubator manager: Creates environments where novel health solutions can be developed and tested.

The global health field offers numerous pathways to create meaningful impact. The most effective route will depend on your combination of skills, interests and values. Consider where you can leverage your strengths to address critical gaps, and be strategic about building expertise in high-leverage areas.

Resources for Global Health Careers

Probably Good - Global Health & Development: An Impact-Focused Overview

A good summary including career, donation resources and a job board

Career profiles on development economics, nonprofit entrepreneurship and Civil Service in LMICs

Personal advising service

80,000 Hours - Global Health

Summary including updated job board just for GH&D

MIT MicroMaster programs in data, economics, and design of policy

JPALs online courses on impact evaluation

The Global Health Network Training Centre - offers extensive catalogue of resources from courses to toolkits, covering a wide range of health research topics

University of Aberdeen - Randomised Controlled Trials online short course at Masters level, teaching how to design and implement RCTs from start to finish

Cochrane - global independent network providing evidence through systematic reviews

VoxDev - features research on global poverty, development economics, and evidence-based interventions

EA Forum Global Health & Development section - discusses effective altruism approaches to development

High Impact Medicine - Impactful medical careers

3ie - International Initiative for Impact Evaluation

World Health Organization - UN specialised agency that sets international health standards, provides technical assistance to countries and collects global health data

Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations - Foundation that finances independent research projects to develop vaccines against emerging infectious diseases, focused on WHO's blueprint priority diseases

Ambitious Impact - Provides people with training, research and funding to tackle the world's biggest problems through a variety of programs - charity entrepreneurship, founding for good, research, foundation

GAVI - The vaccine alliance

The Global Fund - Invests more than $5 billion a year to defeat HIV, TB and malaria

Foundations

Gates ~$8-9 billion per year, now aiming to spend down by 2045, which would suggest yearly spending of ~$10 billion

Novo Nordisk ~ $160+ billion in total funds

Wellcome Trust ~$1.6 billion per year

Questions for Week 2

Feel free to come up with your own questions or take 1 or 2 from each section when reflecting on the material from this week.

Overall Reflection

What surprised you most about the evolution of evidence-based approaches in global health and development?

Which examples from the module challenge your previous assumptions about how we should evaluate and implement interventions?

What do you see as the most significant contributions of the "evidence revolution" to global health?

What important perspectives or approaches to evidence generation do you think are missing from current practice (or from this post)?

How have your views on evidence, and global health changed since you first heard about these concepts? (which could be years ago, at least 20 in my case)

Have you ever strongly believed in an approach that later evidence proved ineffective? How did that change your thinking?

Evidence Quality and Methods

Which forms of evidence do you find most compelling, and why?

How do we balance the desire for evidence with the need for action?

What role, if any, should local knowledge play alongside formal evaluation methods?

What blindspots may exist in current evidence-based approaches?

To what extent can subjective experiences be integrated into evidence-based frameworks?

Would you rather have perfect evidence about a moderately effective intervention or limited evidence about a potentially revolutionary one?

Is it worse to implement an intervention without evidence or to withhold a promising intervention while waiting for more evidence?

How should we weigh evidence-based interventions that benefit current generations versus future ones?

How might different discount rates alter priorities in global health decisions?

Prioritisation and Resource Allocation

How can we account for interventions whose benefits are difficult to quantify?

How should we weigh measurable impacts against potential long-term, systemic changes?

If you were allocating a limited health budget, what evidence would you find most persuasive?

What role should governments, NGOs and the private sector play in scaling proven interventions?

How do power dynamics influence what gets researched and implemented in global development?

What areas in global development are currently underfunded relative to their potential impact?

How do geopolitical interests shape global health priorities and evidence generation?

When is it justified to implement interventions without robust evidence?

Future Impact

Which areas of global health do you think will be most neglected in 5/10 years time?

How might new technologies change our ability to measure impact?

What boundaries should guide AI applications in global health, and how do they trade off against providing benefits?

How should we evaluate interventions with positive health outcomes but negative environmental impacts?

Careers

What skills or knowledge areas seem most valuable for someone wanting to contribute effectively to global health over the next 10/20 years?

Which of the careers described above appeal to you most, if any, and why?

What skills and/or experience should you personally develop if you wanted to contribute to this area?

Feedback

What would you say is missing from this week's content?

What questions are missing from this list?

What further readings, videos or resources would you add?

Further Reading

Why Hasn’t the World Eradicated Polio?

VoxDev - The future of evidence-based policymaking and international development

Global Health Economics Hub - a community of international health researchers working to support health economics research capability and its use within policy in lower-income settings

80,000 Hours Podcast - Eva Vivalt’s research suggests social science findings don’t generalize. So evidence-based development – what is it good for?

Angus Deaton & Nancy Cartwright - Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials

Lant Pritchett & Justin Sandefur - Context Matters for Size: Why External Validity Claims and Development Practice Don't Mix

Mary Ann Bates & Rachel Glennerster - The Generalizability Puzzle - Rigorous impact evaluations tell us a lot about the world, not just the particular contexts in which they are conducted.

Universities prioritised established curricula and traditional disciplines like theology, law and (observation based) medicine

A QALY is a measure of health outcome that combines the length of life with its quality (or well-being). It represents one year of life in perfect health. QALYs are used to assess the benefit of medical interventions by estimating the number of additional years of life gained due to the intervention, weighted by the quality of those years. A year lived in less-than-perfect health receives a value between 0 and 1. QALYs are often used in cost-effectiveness analysis to compare the value of different medical treatments or public health interventions

A DALY is a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability or early death. One DALY represents one lost year of healthy life. DALYs are calculated by summing the years of life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality and the years lived with disability (YLD) due to prevalent cases of the disease or health condition in a population. DALYs allow for comparisons of the burden of different diseases and risk factors, and are used to prioritise health interventions and research efforts

A WALY is a newer metric that extends the concept of QALYs by incorporating subjective well-being as a key dimension. It aims to capture not only the health-related quality of life but also the broader aspects of an individual's well-being, such as happiness, life satisfaction, and social connections. WALYs are calculated by weighting years of life by a well-being score, reflecting an individual's overall sense of flourishing. This metric is particularly relevant for evaluating interventions that aim to improve mental health, social support, and overall life satisfaction, in addition to physical health

“The cases were as similar as I could have them. They all in general had putrid gums, the spots and lassitude, with weakness of their knees. They lay together in one place, being a proper apartment of the sick in the fore-hold; and had one diet common to all”